OWS - Occupy Wall Street

- zuccaccia

- 17 apr 2021

- Tempo di lettura: 6 min

Aggiornamento: 1 feb

Title: OWS - Occupy Wall Street

Photographer(s): Robert Dunn

Writer(s):

Designer(s): Robert Dunn

Publisher(s): Coral Press Art, New York, U.S.A.

Year: 2012

Print run:

Language(s): English

Pages: 52

Size: 14 x 21,5 cm

Binding: Softcover with staples

Edition:

Print: Conveyor Arts, U.S.A.

Nation(s) and year(s) of Protest: U.S.A., 2011

ISBN:

How I Came to Make My Photobook OWS

The following is an excerpt from Robert Dunn’s forthcoming book Mirrors and Smoke, How I Became a Photographer, to be published in late 2021–early 2022.

OWS stands for Occupy Wall Street, the two-month occupation of Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan, and it was going on in the fall of 2011, six months after I got my Fuji X100 camera. I first took the subway down there in late September, to donate copies of a novel of mine, Look at Flower, to the free library I’d heard they had there. Look at Flower is about a hippie chick, Flower Evans, and her adventures in 1967 with the Grateful Dead and the whole counterculture scene, and I thought it would find some readers. Indeed, Wavy Gravy himself said of my novel, “For those youth seeking date of their elders, here lies the anatomy of a hippie chick. Check it out!”. I went to college at UC Berkeley at the tail end of the Sixties, and the first thing I noticed at Zuccotti Park was that the atmosphere there, the very air, was the closest to what I recalled from Berkeley all those decades back. It’s hard to describe, but I felt I was in the same kind of space as Cal was during its own days of rage in spring 1970 … and I’d known nothing like it since. (I’m reminded of how, in the early ’80s I was walking up First Avenue, around the corner from my then apartment on East 11th Street, and I heard two men walking in front of me arguing about the Vietnam War. How strange, I remember thinking. This is Reagan-Bush-Yuppie times, and somebody’s still arguing as if it’s 1973. How cool. Turned out the two men were the poet Allen Ginsburg and a pal.)

So there I was at Zuccotti Park, filled with protestors in tent encampments, marching about, passing out leaflets, selling buttons, doing their best to call attention to profound inequities in American class structure. I of course had my camera with me. By this point I didn’t go anywhere without it except maybe to walk the dog or get a loaf of bread from the local market. And around me I saw nothing but pictures.I wasn’t the only one with a camera, of course. This was a big news event, at a minimum; and something nobody had seen on the streets of America in decades. That first day a lot of people had cameras. (During later visits, the proportion of people there to take pictures to people actually protesting grew noticeably; a reasonable indication of when a political movement is losing potency: more observers than activists.) I did notice one thing with the camera people, they all were shooting pretty much the same stuff. I discovered a great lesson. All those cameras were pointed in the same direction, toward the angry yelling man, the crazily costumed kid, the flood of handmade signs, the sea of sleeping bags all spread out. They were all taking the same pictures.

My job, I told myself, was to take different ones. I’d bring my fascination with color, light, drama to what I shot. In my first picture that day the frame was two-thirds filled with crinkled blue tarp, out of which we see a man’s bare calf above black socks, his hand rubbing his skin. Just that flash of human amidst the flood of color.I kept going. Those large blue tarps fascinated me, the expanse of color, and I took another shot with the tarp prominent, with a red blanket visible in an opening, two guys talking behind it, and—all important—a taped-to-the-tarp piece of paper with the words become your dream above a drawing of a bird and the tag “—De La Vega.” My pictures weren’t all Rothko-like patterns of color, there were a lot of shots of people. As always, I tried to fill the frame in the most interesting way, with the greatest number of interesting moves and patterns, what I had learned from Cartier-Bresson. One of my favorites in OWS is of a man with his hands cupped before his mouth, his head dead center before a floating red balloon, a woman to the right in a yellow New York sweatshirt, the look on her face one of curiosity and startlement, and she balanced out by another woman gazing with mysterious passion almost straight toward my camera. Not so much newsy shots as shots composed like paintings.

Though there were plenty of newsy photos, too. The panoply of characters in the Square, the range of emotions, and lots of photos of the daily lives being lived outdoors in September and October in New York City. I wasn’t a journalist; usually I was down there on a long detour before teaching my New School writing course on Thursday evenings. I’d try to stop in once a week. After I found those copies of Look at Flower had left the on-site library, I donated a few copies of another novel, Meet the Annas.

And I kept taking photos. I thought they were good. I believed they weren’t like everyone else’s photos. I knew the event itself was important, historic. I was becoming fascinated by photobooks … and knew it was time to make my first serious one, actually produced by an actual printer, Conveyor Arts across the river in New Jersey. I sorted photos in Lightroom, moved them back and forth, then leapt into InDesign to lay out the book. It would be paperback, zinelike in honor of its subject (and to keep costs down). I did the full layout myself, designed the cover … I wasn’t just a writer any longer, I was a book designer, too. I took it all over to Jersey City on a PATH train, eating great Indian food on the way; and a few weeks later I had fifty copies of OWS. I took them to the bookstores I was getting to be known at for my interest in photobooks (and no doubt my many purchases). To my unforgettable joy the store managers liked the book a lot, and took copies. Everybody did: ICP, Dashwood, the Strand. Then I went to places I wasn’t at all known. Most memorable was the bookstore at the New Museum on Bowery. The manager there said, “We don’t take photobooks here. We’re not that kind of—” Then he looked at OWS and said, “But I’ll take these. They’re really good. I haven’t seen anything like it.”The book sold, too. Soon I was into a second printing. St. Marks Bookstore, long may it live in memory, took copies, put them out prominently. Spoonbill and Sugartown in Williamsburg. The activist bookstore Bluestockings on the Lower East Side, too. Pretty much everywhere I went.

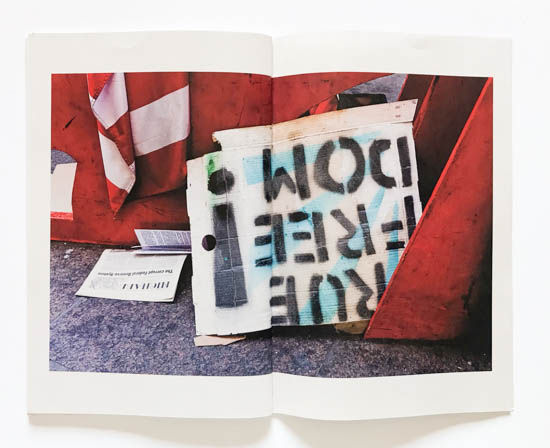

This was self-producing a photobook, and it was so easy! (Hah.) All successes have their odd turns. The manager of the International Center of Photography bookstore told me that ICP was going to have a show of photos around Occupy Wall Street, and that I should submit some of the ones from my book. I did. They took one, the final photo in the book, blocks of red, a dangling American flag, and words stenciled on corrugated cardboard that read:

True

Free

Dom … with a big back exclamation point to the side.

What I liked about this photo was that the sign was upside down, you had to read it from the ground up, and work a little to make out what it said. Something about it being upside down added more significance, even if I couldn’t explain it. The show was to be on Governors Island, a ferry ride away from the southern tip of Manhattan. On a fall day a year from the events in Zuccotti Park I made my way to the island, then hiked all the way across it to see the show. There was my name, Robert Dunn, on the list of photographers with work in the show. And there was my photo of the stenciled sign, True Free Dom! … hung right side up. My photo, again, had the words upside down, but the curators had flipped it over so that it was easy to read. The lack of mystery, of complication, in the photo was palpable, at least to me. Here was my first photo in a major show and they’d hung it wrong.

A shrug. What can I say. There was nobody there to complain to, so, yeah, a long shrug … and a long trip back across Governors Island, a long ferry trip, and a long subway ride back home.

Comments